Another fasting experience shared

Jeanette Winterson: why I fasted for 11 days

“‘Eating too much these days is normal. Not eating, unless it’s the latest diet or celebrity detox, puts you in the box with the weirdos. Or the secretly anorexic … ”

Earlier this year, feeling tired and stressed, and disturbed by our culture of overconsumption, I decided to try fasting – a practice going back millennia. The results were surprising and now I can’t wait to do it again.

Everybody knows about fast food. Scoffing that factory blend of hormone-heavy protein, sluggish starch, industrial trans-fats and E-numbers is the reason why most people have also heard of the Fast Diet, “5:2”, where you restrict your calorie intake by three-quarters for two days a week. Not many people, though, have ever really fasted; that is, given up food completely for a length of time.

When I decided to embark on an 11‑day fast, my friends decided I had gone crazy. Eleven days with no food? Why would anybody want to do that?

Their response was interesting. What if I had said I was going on a gourmet holiday for a fortnight, munching my way through the Michelin stars? That would have been normal. Eating is normal. Eating too much these days is normal. Not eating, unless it’s the latest diet or celebrity detox, puts you in the box with the weirdos. Or the secretly anorexic.

I discovered that the very thought of not eating makes people anxious. Food is comfort. Food is safety. Food is plenty. Food is how we mark the divisions of each day. Or as Leonard Cohen put it – humans are always looking for things to do between meals.

Fasting is not new. Religions of every kind have had fasting in their calendars forever. Jesus fasted for 40 days and 40 nights before he began his ministry. This is the inspiration for Lent – six weeks of food restriction before the feast of Easter Day.

The prophets and patriarchs of Judaism spent a lot of the Old Testament fasting – squaring up to a bad-tempered despot such as Yahweh seemed to work better on an empty stomach. Or to precis Freud, a latter-day Jew: don’t overfeed your controlling super-ego.

In the Islamic tradition, the fast of Ramadan forbids daily eating until sundown – and then only a modest meal should be consumed. The prophet Muhammad declared that while prayer takes the believer halfway towards Allah, fasting completes the journey.

Hindus regularly observe dawn-till-dusk fasts, 12-hour respites for the body that allow the internal organs a welcome rest from their duties as a processing plant. The 5,000-year-old Hindu method of natural health, Ayurveda, uses fasting to balance the body, concentrating on digestion and elimination.

Buddhism, naturally, prefers a middle way of no excess: not too much food, not too little. The Buddha himself began by road-testing extremes – all the wine, women and curry nights a young man could want, followed by years of self-denial. But the Buddha didn’t reach enlightenment through fasting – only after he was commanded to eat. Even so, Buddhist monks are encouraged not to eat solid food after midday – both to rest the internal organs and to concentrate the mind on higher things.

The religious and mystical point is that human beings are not just what we eat – remember that bit in the Bible, “Man shall not live by bread alone”. We are more than food, more than reproduction, more than survival. We have creativity, curiosity, a need for meaning, and the strange desire to put ourselves at risk, both to discover our limits and to get beyond them.

No matter how comfortable our lives, it is hard to be happy without challenge or meaning. Having plenty of stuff is never enough. This isn’t discontent; it is the oddity of being human. Our species’ long and stubborn belief in an afterlife can be put down to superstition, terror, ignorance or magical thinking, or you could see it as a conclusion reached by the only organism on the planet that feels itself to be more than its body. The body dies, the spirit continues. That this must be so makes more intuitive sense for many people than the empirical truth that it is not so.

I discovered that the very thought of not eating makes people anxious. Food is comfort. Food is safety. Food is plenty.

Some people go on retreats or try to connect in other ways with the part of themselves not expressed by the frantic, full-on world of getting and spending. Fasting does that by making the body itself the site of retreat.

Gluttony is one of the seven deadly sins. Dante puts his gluttons in the third circle of the Inferno – writhing 24/7 in a whirlpool mudbath of live intestines and excrement. Does that seem an over harsh judgment on a life spent ordering supersize cokes, buckets of fries and vats of gelato? Given the way we live now, the gluttony debate in Christian thought looks like a proto-Marxist prophecy against the overconsumption we have learned to call capitalism. Overconsumption that wrecks the planet and unbalances our relationships, nation to nation, class to class – and with one another.

The greed-is-good philosophy of the Reagan/Thatcher era – 30 years of stuffing your face followed by economic collapse – is the macro model of what happens in our bodies. We are not designed for “all you can eat”.

True, some of the best conversations happen over a good meal and a bottle of wine. Food is fabulous. But too much eating of too much easy food too much of the time is partly responsible for our current level of degenerative disease – diabetes, heart conditions, fatty liver, hypertension, inflammation and, of course, the rise and rise of obesity. Yes, this is about the sort of food we eat, but it is also about the quantity of food we eat. Many of us are gluttons.

And reaching for the next piece of cake when we’re stressed or miserable solves nothing, as anyone working with eating disorders knows. As my wife Susie Orbach puts it: “Feelings don’t live in the fridge.”

At the other extreme, anorexia is as much about disgust as about control. Take a day noticing how bombarded we are with food – not just what we actually eat, but the advertising, the supermarkets, the sweets at the petrol station, the wrappers and litter and overflowing bins. A young friend of mine who used to be anorexic told me she hated how her parents were always eating – and soon she hated how everybody was always eating. And then she hated herself if she ate.

Interestingly, the therapeutic clinic that I attended – the Buchinger Wilhelmi Clinic in Überlingen, run by doctors – is good for anorexics. There is no food – though anorexics undergoing treatment there are, of course, fed. But the doctors told me that the relief experienced away from food is part of the healthy impulse back towards food.

It’s important to say that fasting is not starvation. The anxiety and fear that attend lack of food in critical circumstances of famine or enforced deprivation are not present if you are fasting voluntarily. Nor are you beating up your body to get it in line. You are in control, but this is a partnership – your body and you. When I began reading about fasting, before it was my turn to try it, I found that religious visionaries such as St John of the Cross, St Augustine, Hildegard of Bingen and Julian of Norwich all recommended fasting as a way to clear the head and concentrate. Gandhi fasted in order to focus his mind. Pythagoras refused to accept anyone into his school who did not know how to fast.

The Greeks intrigued me. Our religions are imports from the east where ascetic practice is normal, so I would expect to find a tradition of fasting there, but the Greeks were rationalists, the founders of western medicine. But here are Plato and Socrates fasting for mental efficiency, Plutarch advocating a day of fasting for any minor disorder, and Hippocrates saying that “to eat when you are sick is to feed your sickness”.

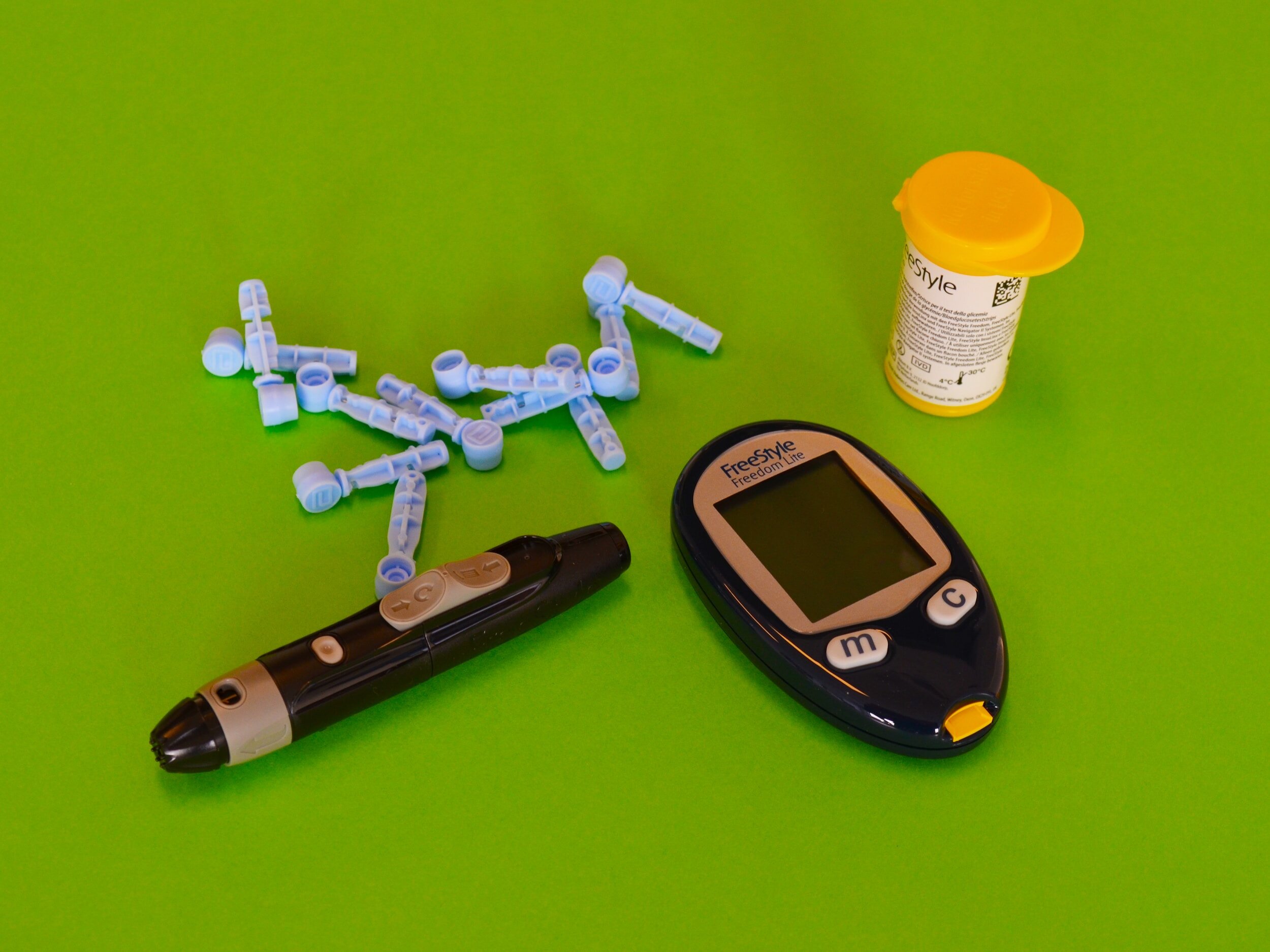

I wasn’t sick but I did have high hereditary cholesterol. I am the right weight, I’m fit and I have more good cholesterol (HDL) than bad (LDL), but there is a history of heart disease and early death in my biological family. I was determined not to go on statins. I did my own research and could see that while the drug companies are pushing to get more of us on the pills, there is mounting evidence against taking them, unless there is no alternative. At my local GP practice, a few of the overworked doctors act like the robot arm of Big Pharma – if it squeaks, drug it.

But I was under a lot of stress and I knew my cortisol was too high. Back in March, I was exhausted. My dear friend Ruth Rendell had been in hospital for three months, and I was commuting between Manchester University, my home in the Cotswolds, and Ruth’s hospital bed in London, as well as trying to finish a book due for October publication and prepare for my marriage in June. I was feeling overwhelmed.

At this point many people either eat or drink too much. I suddenly had the idea that I should do the opposite.

Michael Mosley, the man behind the 5:2 diet, has written about the positive effects of fasting on insulin levels, triglycerides, cortisol and cholesterol, and levels of energy. So knowing that I am a person who likes extremes, I thought, why not? And that’s how I found myself heading to the Buchinger.

The clinic was set up in 1953 by Otto Buchinger, a German doctor who had been discharged from the Imperial German Navy in 1919 with chronic rheumatism of the joints caused by septicaemia. Unable to move without agonising pain, a life in a wheelchair awaited him. He decided to fast for a month and emerged utterly weak but fully mobile. For the rest of his life, into his 80s, he researched the fasting principle.

So what happens when we stop eating? The body first uses up the glycogen stores in the liver. That might take 12 hours, or 24 hours. Afterwards, the body will have to use proteins (muscles) or lipids (fats) to produce the energy (glucose) it needs. The body is programmed to avoid breaking down muscle, and so the liver turns into a factory to manufacture ketones for fuel. That’s where all those hokum diets with raspberries and ketone pills come from. But you don’t need to buy anything; just stop eating and your body will do the work for you.

This is where the process gets exciting. Imagine your house is freezing and you have to burn the furniture to keep warm. First you burn the rubbish, stuff you have been hoarding for years and don’t really need. The body does the same. Sick cells, old cells, decomposed tissues, are burned away. This is the ultimate spring clean. It allows the body to eliminate toxins and metabolic waste at the same time as turning them into heat and energy. And you can live off this rubbish for days.

Next, the body will go for its fat reserves. Most of us have plenty of fat for the body to get busy on – and belly fat is an easy target. As one doctor at the clinic told me: “You haven’t stopped eating – only you are eating from the inside for now.”

But the process of ketosis is more than the body eating itself. While fasting, the body goes into repair mode. Valter Longo, professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California, believes that this protective repairing mechanism is the result of our 3m years of evolution. His ongoing research shows that fasting actively reboots the immune system and leads to a drop in IGF-1, a growth hormone linked to ageing, insulin resistance and tumour progression. There is an impressive documentary available on YouTube called The Science of Fasting. It begins with research carried out over 50 years in the Soviet Union, and until recently unavailable in the west. There, doctors discovered that fasting could successfully treat chronic asthma with a cure rate pharmaceuticals would kill for.

But that’s the problem: fasting is free. Well, it’s not free, because you need to be medically supervised, at least to begin with, but there’s no money in it for Big Pharma. As Dr Andreas Michalsen from the Charité hospital, Berlin – Europe’s largest public hospital, and one that treats more than 500 patients a year with fasting – explains in The Science of Fasting: “If I had been studying a new drug and got these results, I would be getting phone calls every day. It is very easy for critics to say there are not enough studies when we know there is no funding for these studies.”

So how do you feel when you fast – you, the person used to having a good relationship with a full fridge?

The first three days are difficult. Emotionally and physically. The Buchinger method encourages you to accept the mood swings and create an attitude of acceptance and tolerance in yourself; you are working with your body not against it. In the early mornings patient meditate. Exercise classes begin at 8am and run through the day, including long walks and personal training in the gym. Exercise is as important as mindfulness. It keeps the metabolic rate high and encourages the body to move towards a state of maximum efficiency. After all, when we were coping with food shortages in the past, we had to keep moving to find something to eat. Sitting in your room feeling terrible is not the answer.

It helps if you know you are in safe hands. On arrival at Buchinger, patients are given a full set of blood tests and a consultation with a doctor, and every morning a nurse checks your blood pressure and general health. Day three is crisis day as the body moves into full ketone production. I felt cold, withdrawn and a little light-headed. But day four was a revelation: I woke early, clear-eyed, cheerful and full of energy. This continued right through my fast. I was able to concentrate, take long walks and go to the gym. I wasn’t hungry for the next six days. My blood pressure was stable throughout, and I was enjoying myself. When the time came to break the fast – something that has to be done most carefully with tiny amounts of solid food – I really wanted to continue, just to see what would happen next.

When my cholesterol was measured it was down from 7.9 to 6.2, and with the “good” cholesterol in the right ratio. Three months later it is stable. Cortisol is back in the normal range. Joint pain in my foot following an operation last year has disappeared completely. If you have weight to lose, you will lose it. If you have less weight to lose, the body seems to know how to balance itself there too.

Fasting isn’t a diet. It isn’t calorie restriction. After fasting you will return to eating normally, though with adjustments where necessary. But the idea is that while you fast your body will undergo profound changes that last after the fast is ended. Improvements can be maintained through diet and by making fasting a normal part of life – as it once was.

Most impressive among the people I talked to at the clinic were the regular visitors for rheumatism and arthritis. Quite a number are fortunate enough to have the resources to come a couple of times a year, to fast for two weeks each time, and they have seen a drastic reduction in medication and pain, and a significant increase in joint mobility. The answer seems to lie with fasting’s ability to decrease intestinal permeability – the “leaky gut” problem so often associated with inflammatory diseases, as large molecules acting as antigens pass through the intestinal wall and cause immune reactions. Eighty per cent of our immune system is in our gut. If the gut is wrong, we are wrong. Fasting is good for your gut.

I would like to experience the profound sense of wellbeing and peace of mind that fasting delivered again. And I had more time – think how much time shopping, cooking, eating and clearing up afterwards takes out of every day. Suddenly there was time to think deeply, to read, reassess, be with yourself, and to make a new friend of your body.